Andrea

Urban school districts across the US have long struggled to close the achievement gap for poor students in low-performing schools. Over the past decade, there has been an increasing turn to what Osborne and Gaebler might call “public entrepreneurial management” (4), as school districts have been reorganized, and charter schools have created competition for traditional public schools.

Last fall, Tennessee created an Achievement School District — a special state-run district for the state’s lowest performing schools. This district was created as part of the state’s effort to qualify for a federal Race to the Top grant, which is given to states making strides towards innovative education policy reform. The New York Times calls Tennessee’s Achievement School District is “a petri dish of practices favored by date-driven reformers across the country.” The majority of the schools in the district will be run by charter school operators, and will emphasize frequent testing and data analysis.

Encouraging policy innovation to change dysfunctional systems is certainly an improvement from the status quo of failing schools, but at the same time, the question of feasibility and the ability to effect long-term positive change hangs over all policy decision-making. Implementation strategies must achieve the balance between visionary, often idealistic, policy proposals, and existing realities on the ground. Change to the status quo is often resisted by people currently in-trenched in the system, both the “street-level bureaucrats” (in this case, educators and school administrators) and consumers (parents, students, taxpayers) of the public school system.

The first wave of implementation theory literature, produced in the 1970s, criticized the “top down” approach to policy implementation. Pressman and Wildavsky’s 1973 text Implementation spoke to the fact the policy reforms being passed at the “top” level, by politicians and senior bureaucrats are often not carried out as prescribed on the ground, and that policies are often developed without sensitivity to local cultural circumstances or histories. Resentment towards new authority and fear of exclusion often drive much of the opposition to sweeping policy reform at the “bottom,” or local level. Four decades later, Tennessee’s Achievement School District is plagued by much of the same “top down” criticism. Despite signs of progress in student achievement in the first seven months of the district’s existence, the community has also voiced concern about racially insensitive policies, and the sidelining of experienced teachers.

Yet, in Tennessee, all stakeholders, no matter whether they support or oppose the reforms, also know that the current system is not working. The need for innovation is evident. In their discussion of how to successfully implement change, Howlett and Ramesh (2009) outline policy subsystems as an important component of successful implementation; subsystems shape the evolution of the programs for implementing policy decisions (161). Bureaucrats are the primary actors of implementation, along with multiple levels of government, which support the executionary power of the bureaucrats.

In the Tennessee Achievement School District, charter schools operators act as implementation bureaucrats. They run the schools in collaboration with the state; with the authority of the state behind them, the chart operators have implemented new disciplinary policies, including some that have been interpreted as racially or culturally insensitive. They have hired new teachers, many young and inexperienced recruits from a state fellowship program and Teach for America. In some Achievement School District schools, no teachers remain from the previous academic year.

While some actions have rightfully provoked community criticism, the successful push to improve student test scores demonstrates the positive outcomes of this goal-driven entrepreneurial approach to government, which focus on improving tangible outcomes like higher test scores. The new policy bureaucrats have been inarguably successful in introducing innovative policies that have helped produce desired results. Next, perhaps, policymakers must work to develop implementation strategies that produce measurable improvements and improved without sacrificing cultural sensitivity.

Resources

Howlett, Michael and M. Ramesh. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems, Oxford University Press, 2009 (3rd Edition).

Osbourne, David and Ted Gaebler, Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector, Introduction and Chapter 11, Addison-Welsey, 1992.

Pressman, Jeffrey L. and Aaron Wildavsky. Implementation, University of California Press, 1984

Rich, Motoko. “Crucible of Change in Memphis as State Takes On Failing Schools.” The New York Times. April 2, 2013.

Policy literature and analysis have been primarily interested in understanding the various steps of the policy process. From the identification of a specific issue, the inception of a particular policy, its implementation and outcomes, the analysis of the policy stages tends to focus on a macro-level. But what seems to be often missing from such analyses is how an actual policy is implemented on the micro scale, at the day-to-day basis. Indeed, in most cases, the way policies are implemented has a lot to do with the bureaucratic realities that are often unrelated to the actual policy. Under this view, one can argue that – at least to a certain extent - policy implementation is determined by policy interpretation. This interpretation process is not undertaken at a high-level decision-making, but usually performed at the lower levels of the bureaucratic machine. It is at this critical stage and through the frictions between policy implementers and citizens that a particular policy gets tested for the first time, not so much in terms of its expected outcomes but more so in terms of its feasibility and responsiveness to a particular situation, population, city or state. In that sense, policies are often adapted to reflect the realities on the ground, which are omitted through previous stages of the policy process. In many regards, successful adaptation can lead to successful implementation but not necessarily to successful outcomes.

Lipsky (1980) and Pressman and Wildavsky (1984), reveal the intricacies related with street bureaucracy and policy implementation. For Lipsky, street-level bureaucrats often work in situations too complicated to reduce to programmatic formats, under conditions that often require responses to the human dimensions of situations (1980:15). Under these conditions, the frictions between the policy’s stated objectives and the actual application of a given policy can create situations where interpretation is solely based on the street bureaucrat or on a given authority. Perhaps the EDA employment program in Oakland stumbled across these interpretational frictions; while the objective was to raise employment, the implementing authority and street-level bureaucracy (if we take the freedom to consider EDA as such) instead of taking the direct path of paying the employers a subsidy on wages after they have hired minority personnel, expanded their capital on the promise that they would later hire the right people. For Pressman and Wildavsky (1984) the difficulties in achieving the actual outcomes (increased employment opportunities for minorities) were rooted on the organizational tradition of EDA. One can also argue that such difficulties were enhanced through EDA’s misreading of important realities in Oakland, namely the city’s transition from a manufacturing to a service center and the disconnect between unemployed manufacturing labor force and service seeking employees jobs.

But certainly Oakland’s example reveals a more general misconception in terms of policy implementation. For instance, in many cities facing a housing problem, housing programs often do not manage to fulfill their objectives as subsidies are designed in such a way that the intended beneficiaries do not benefit from the program. An extensive literature on slum upgrading describes various cases were subsidies were captured by contractors or higher income segments of the city’s population instead of the intended low-income dwellers. In post-Apartheid South Africa housing became a constitutional right with the government under the obligation to provide these rights “within reasonable means”. This constitutional amendment was realized through a generous housing policy that was implemented in order to fulfill the residential backlog. But the generous housing subsidies (reaching $15,000 per household) were often captured by middle-income citizens and usually not by the intended beneficiaries who were the poorest citizens. Paradoxically, a housing policy aiming to erase inequalities based on Apartheid has, through its implementation, perpetuated inequality. On the long run, the South African government has spend important amounts with the perverse effect of reinforcing the spatial logic of apartheid and by continuing to settle poor (and almost entirely non-white) communities on the periphery of cities, missing a great opportunity to break down racial segregation and economic marginalization.

The example above raises an important question: what is the role of the street level bureaucrat? In other words, can this process of policy interpretation as performed by street bureaucracies correct for the fallacies within the macro-level decision making of a policy. Certainly an answer to these questions varies on a case-by-case basis. But what seems quite clear is that although the leverage and influence that street bureaucrats might have depends on specific situations, their role as state representatives and actual implementers provides them with important insights on how an actual policy could perform. In that sense, street bureaucracy offers the “bridge” between policy makers and citizens. If understood as such, street bureaucracy can create better connections between the macro-level and the day to day of policy decisions.

References

Lipsky, Michael, Street Level Bureaucracy, Russell Sage Foundation, 1980.

Pressman and Wildavsky, Implementation, University of California Press, 1984.

There is indeed a need for a paradigm shift in the practice of governance in the United States. No one is utterly satisfied with the way government is conducting its business. There is an across-ideology consensus that government should be free from special interests if it must operate effectively. To this, Osborne and Gaebler, the authors of the oft-cited book “Reinventing Government,” are absolutely right in alluding to Thomas Khun’s beloved concept: “paradigm shift”. Now, where controversy arises is whether the public spirit that guides government action should be converted into an entrepreneurial spirit where priorities are defined by competition or by what Hirschman calls “the availability of exit.”

Osborne and Gaebler’s book was first published in 1992. At that time, although the Democratic Party was in power, the revolution launched by the Reaganism in the 1980s to shrink the size of government was still in full-fledge effect. Al Gore, Clinton’s vice president, instituted what is known as National Partnership for Reinventing Government (NPR) on March 3, 1993. And the goal, as stated, was to “make the entire federal government less expensive and more efficient, and to change the culture of our national bureaucracy away from complacency and entitlement toward initiative and empowerment.” In other words, to use Osborne and Gaebler’s methaphor, government henceforth must steer not row. Government action should be reduced in a mere role of guiding and to a certain extent coordinating. Government agencies, the bureaucracy, should be defined in a competitive way; merit-based performance is the sole benchmark. Contracting out, privatization, competition to mention just three, constituted the new lexicon.

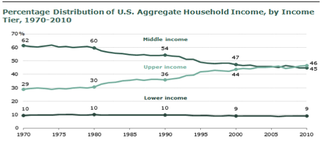

When, however, this new way of governance is scrutinized against empirical evidence, the results leave much to be desired. Research shows that the financial crisis that hit the country in 2008 with worldwide consequences is the result of this governance approach. The steering, or the passive role, of government in the financial sector (particularly the repeal of the Glass-Steagal Act) is considered to be the principal factor that led the world to the brink of this financial mess. Moreover, all statistical data seem to concur that from the 1950s to 1970s, when state interventionism was at its height, meaning when government was rowing, inequality of wealth and income was very moderate compared to the Reagan-Thatcher during which the legacy of the New Deals had been rolled back (Krugman, 2007). Figure 1 below shows the occurrence of a major shift in the income distribution after 1970. The 2012 Pew Research Center Report shows that upper-income households, as a proportion U.S. aggregate income, increase by 59% from 29% in 1970 to 46% of in 2010. Whereas, the share of the aggregate income by middle-income households decreases by 28% from 62% in 1970 to 45% in 2010. This situation is, according to many (Krugman, 2012; Stiglitz, 2012), associated with this model of governance.

As it happens, the claim to transform government into a market-like machine does not withstand empirical evidence and the practice falls short of expectations. The public sector is in essence different from other types of market organizations. While the market’s main function is to maximize net monetary benefit, protecting and promoting the public interest is (or should be) the core of all government action. Osborne and Gaebler’s entrepreneurial spirit paradigm aims at devising countless exit opportunities for the people in all settings: education, health, criminal justice, to mention a few. This should not be seen as bad propositions. After all, the American system is rooted in the tradition of finding exit opportunities for the people. However, as Hirschman adroitly points out, because they are usually made only on a short-run private interest calculus, individual exit decisions, in their aggregate effect, are harmful. For example, Hirschman says, “after an incipient deterioration of public schools or inner cities, the availability of private schools or suburban housing would lead, via exit, to further deterioration.” The existence of exit can, as it is often the case, impede voice that might be the best way for reform.

By Claude Joseph

Comment by Jermaine

Thanks for raising some of the costs of competition. With your post I am reminded of several stories that have come out that tell us about the implications of when the private sector competes and secures government contracts. There have been several stories about rapid increase in private sector run state prisons. While they have gained in securing more contracts, they have also gained by lowering the quality of service. Prisoners face telephone charges that are not competitive; prisoners are missing out on access to basic health services.

When you discuss policy directives in development circles words like project management, stakeholders, target groups/beneficiaries, participatory monitoring and evaluation and program design, baselines, and adaptability studies, will be thrown around. Often times, policies are adapted to be used in a different country than it was initially designed for, and that adaptation can include many interested parties take part including ministries, large international NGOs, finance organizations, influential worker and education organizations, and other stakeholders, or not. This is not to say that the decision about which policies will be pursued and programs implemented is participatory, nor is it always unilateral, but that there are diverse influences in such policy design, even in adaptation, who should not be discounted. The diffusive process of policies in the implementation stage without proper adaptation can be detrimental to the newly identified target group.

The readings this week offered a glimpse of the implementation stage of policy studies. We are offered evaluations of the successes or failures of policies pursued based on the design of the policy (whether it had clarity and was consistent with previous policies); the actors engaged in implementation (state-level bureaucrats, stakeholders and beneficiaries); and the rules of procedures surrounding the implementation (level of decentralization, empowerment of beneficiaries and stakeholders, number of decision-makers). Howlett and Ramesh provide us with this generalization and a brief history of the study of the implementation stage where Osborne argues that through decentralization less bureaucratic and a more entrepreneurial spirit in government may be more beneficial.

Regardling the three generations of implementation studies, Howlett and Ramesh, claim the first generation is defined by Pressman and Wildavsky’s argument that implementation, as a stage heuristic, matters because it can undermine and interpret the goals and priorities of the policies. Looking to Pressman and Wildavsky’s article we see through the ERA program which was rolled-out in Oakland in the 1960s they offered examples of ambiguity of goals, unshared sense of urgency, and lack of cooperative measures between stakeholders, that were part of the ills of the program that led to it’s inability to produce the outcomes it had set out to produce. In generation two of implementation studies that top down approaches are contrasted by more communal approaches to development and in the 3rd generation more testable theories are provided.

In hindsight, it seems common sense to argue that through empowerment and ownership, both centerpieces in the bottom up approaches to implementation, programs that are developed can be sustained in the long-term, which is one of Osborne’s claims. Through a ten-point plan, Osborne argues that governments can be less bureaucratic, centralized and discretionary and become more empowering, enterprising and thus entrepreneurial. The goal is to create “…institutions that empower citizens rather than simply serving them” (Osborne, 15).

This kind of empowerment of beneficiaries to promote development is seen as a bottom up approach to development practices (Howlett and Ramesh). It is a characteristic of the decentralization movement of public schools in metropolitan cities in the United States, including New York. Through decentralization the school board promoted an entrepreneurial culture that afforded schools more control over the everyday task of running the school and less bureaucratic red tape. At the same time, they were held to higher standards of performance and expected to provide more services with the same resources. Schools that had the capacity to take advantage of this new culture succeeded and those who did not were not provided many other resources, and were closed.

Decentralization included increasing school choice by allowing students to vote with their feet through exit, those who could. It is argued that the students who could afford to leave their neighborhood schools did, and this caused a decrease in social capital and creaming negatively affecting the poorest school districts. Through this perspective decentralization of public schools is a top down approach to providing accountability to schools. Whether this policy was a success or failure depends on whom one speaks to. However, it is a good example of how the implementation of a policy might not have considered the stakeholders and beneficiaries, or even teachers as street-level bureaucrats, in the design and implementation stages.

Lastly, although policies generally diffuse between cities, states and nation-states, it is possible that ministries or boards of education would apply a policy that worked in another area. However, without properly adapting it for the newly identified beneficiary/target group and their characteristics (student demographics, testing scores, parental education rates, etc.) this could cause more harm than good.

Kelsey

References

Howlett and Ramesh, Chapter 7: “Policy Implementation.”

Osbourne, David and Ted Gaebler, Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector, Introduction and Chapter 11, Addison-Welsey, 1992.

Pressman J. and Wildavsky A. ( 1973/1984) Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It’s Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation of Ruined Hopes. Berkeley: University of California Press.

In 2011, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a new process for allocation of New York State grants. Rather than releasing Requests for Proposals or announcing grant application periods, 9 of the State’s 13 funding agencies would coordinate their funding cycles to accept grant applications at the same time, via one electronic application process, and applications would be reviewed and awarded simultaneously. Agency control over the funding process would be shared with public-private Regional Economic Development Councils (REDC’s), created by and accountable to the Governor’s office, who would define regional economic priorities and assist in reviewing grant applications. Called the Consolidated Funding Application (CFA) process, this process was ostensibly aimed at reducing the work effort required of applicants to cultivate cross-agency and cross- jurisdictional support for projects, and to unite the funding process behind shared priorities and processes.

The CFA process is designed to facilitate “one-shot” funding efforts. Applicants can apply to the majority of State funding agencies at once, and possibly get their projects moved up the ladder at permitting and regulatory agencies if they are funded. This reduces the significant, cumulative lag time on publicly-funded projects due to sequential efforts to secure funds from different agencies, and subsequently apply for necessary permits or approvals, which are magnified by serial attention from staff members at applying and reviewing parties.

The process was also designed to deliver the benefits of “convening the system”, giving shared responsibility for the creation of project ranking criteria and the design of threshold requirements to State agency grant staff and REDC leaders during a series of mandatory forums. This was intended to reduce the occurrence of interjurisdictional snafus (where projects would be authorized for funding by certain agencies or the REDCs, but be unable to proceed because of regulatory or permit requirements from other agencies) and tie State agency priorities more closely to local economic needs. Agencies and Regional Economic are to review applications for their accordance with regional economic development plans, formulated by REDCs in accordance with guidance from the Governor’s office, in addition to agency priorities. Funded projects that are a part of “Projects of Regional Significance” or other priority status are moved to the top of the permitting and approval list for certain agencies. This allows the State to direct its funding in apparently the most concentrated, bang-for the buck way (projects that do not support regional economic priorities are scored lower, and therefore are less likely to receive funding), and to maintain a procedural focus on the Governors’ priority: economic recovery and expansion.

In conjunction with the development of the new CFA process, Cuomo capitalized on expanded focus on the State budget woes to push though a measure that was previously though to be impossible: he drastically reduced the funding available for discretionary funding by legislators, or ‘member items’, and redirected some of it to the CFA process. This was publicly described as a way to control pork barrel spending: It was aimed at reducing the influence of state legislators in delivering funding to their constituencies without accountability to the governor’s office or State agencies, at disencumbering the passage of day-to-day legislation, and eliminating legislative allocations of funds from State agency budgets for projects which ran counter to their missions or regulations. In a more Machiavellian sense, this also served as an attack on political support for republican legislators who made their names through their abilities to “bring home the bacon” while refusing to work in a bipartisan or inter-branch fashion.

The NYCFA process is still on testing grounds: there have been only two funding rounds so far, and the results of the funded projects i

n terms of procedural perfection and economic returns have yet to be determined. In the end, it could be a model for the federal government and other states to follow in an effort to streamline and unite their own funding processes and priorities, and as a venue to hammer out interagency differences in procedural requirements.

The discussion on policy implementation this week prompts a return to the issue of Healthcare reform in the United States. Osbourne and Gaebler (1992) at the end of their introduction to “Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector” call for “better government…. governance” (Osbourne, Gaebler, pg.24). In this book they present an alternative approach to managing the country affairs “ entrepreneurial government”. In chapter 11 of the same book they demonstrate the merits of this alternative approach to public policy by using HealthCare reform in the United States. Much of what was described in this example resembles ObamaCare, and while this approach to policy in the US health care system is only about 2 years old an examination of it through the lens of Enterprising Spirit outlined by Osbourne and Gaebler might be useful.

Osbourne and Gaebler maintain that in an entrepreneurial health care system government would set the rules for the administration of the system but leave actual provision in private hands. This system would encourage competition-allowing consumers to shop for the best possible prices and make information more easily available. Most importantly this system would create strong incentives for preventative care by encouraging prepaid arrangements between insurers and insured that benefit both. Osbourne and Gaebler maintain that an entrepreneurial health care system would preserve the decentralized nature of the US system while reducing the hierarchy associated with medical care. Creating a perfectly competitive market structure in which increasing quantities of consumers have better access to information, low prices and greater choice among medical practitioners. What they are in fact suggesting is an application of the neo-classical theory of perfect competition to the provision of health care.

Is this simply a theoretical example or can this type of system truly be achieved? The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) is certainly a step in this direction. The aim of Obamacare is to increase health care coverage for Americans while reducing costs. Furthermore the legislation provides a number of mechanisms such as mandates, subsidies and tax credits, which will provide incentive for employers and individuals to increase the coverage rate. In a very liberal market economy such as the US this type of healthcare reform does not seem very radical yet there has been public outcry and opposition to the implementation of this policy. As the pillar of the Capitalist world the entrepreneurial spirit is assumed to permeate through the very fabric of our society yet Obamacare is so strongly opposed. Why?

The health reform proposed by Osbourne and Gaebler is hinged on the very strong assumption that the market maintains supremacy in the provision of goods and services. It is this very assumption that will threaten the success of any type of healthcare reform based on competitive market structure. Two reasons could be offered to explain this opposition. Firstly the health care reform example by Osbourne and Gaebler and the Obamacare reform represents significant government intervention with regulations that alter the incentives of both health care providers and consumers. Since any type of government intervention is viewed within American society generally as infringing on the freedom of the market, a policy aimed at improving the health system by applying market mechanisms will be opposed simply because of what it represents. Secondly one might argue that this intervention into the healthcare system is unwarranted. The main argument for Obamacare and indeed raised by Osbourne and Gaebler is that the American Health care system fails to provide the efficient quantity because the price is simply too high. But is this necessarily a market failure or is it simply a consequence of the natural adjustments of the market forces. Price after all is not intended to drive incentives but rather to act as a signal, individual choices of consumers are assumed to be driven by preferences and income. So the fact that millions of Americans are/were uninsured could simply be explained by the fact that medical care was not a preferred commodity or that their incomes are simply too low.

One wonders then was the problem truly that medical care was priced too high and provision was limited? Or was it the case that incomes are and continue to be too low? Furthermore are these questions linked and the problem is threefold, limited access, high prices and low income? Finally what about consumer preferences? Increased access at lower prices does not guarantee that consumers will choose to purchase health care simply because they can now afford it. While the proposal by Osbourne and Gaebler (1992) and the implementation of the Patient Protection Affordable Care Act (2010) are certainly very good attempts at tackling the health care problems faced by the US, further consideration should be given to this problem particularly in attempting to change the preferences of consumers. As it is unclear thus far that making health care more affordable will lead to increased consumption.

by Deon Gibson

References

Howlett and Ramesh, Chapter 7: “Policy Implementation.”

Osbourne, David and Ted Gaebler, Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector, Introduction and Chapter 11, Addison-Welsey, 1992.

Comment from Zoe:

Osborne and Gaebler do not argue for a purely competitive health care system, but for one in which insurers must accept all patients, thus ending “the current practice of competing for the business of low-risk patients...” They argue that the government should play a larger role in steering health care policy, but a smaller role in financing and that the most fundamental problem with health care is that the United States government does not play a proactive role health policy. This has led to a lack of preventive medicine and other problems. What elements of the Affordable Care Act are truly competitive and what aspects of Osborne and Gaebler’s mode are truly competitive?

Well Zoe:

Adam Smith wrote that government's responsibility was to ensure the efficient functioning of the market as it provides for our needs. To achieve this government would establish a system of property rights, a legal system to enforce these rights and protection of the citizenry. Once these were in place government was to sit back and allow the market to produce the goods desired by society "steering not rowing". This formed the basis of what Paul Samuelson and later Leon Walras referred to as perfect competition in the Theory of the Firm. A market with a huge number of buyers and sellers all selling an identical product each having no influence over the price which is set extremely low to attract customers. I should point out that perfect competition is a theoretical ideal so that it is actually impossible to achieve but it is possible to observe market structures that are similar e.g monopolistic competition. The example that Osborne and Gaebler discuss is in essence a liberalization of the market for health care by increasing the number of people who have access as well as the number of health care providers as this occurs their ability to influence the rate/premium will be reduced. In a similar vein Obamacare is attempting the same result by increasing both the access to health coverage and the number of practioners the price will undoubetedly be driven down. Now I did not say that Osbourne and Gaebler are arguing for a purely competitive health care system but rather the reforms they propose are the result of applying the very basic tenants of perfect competition. In a similar vein the policy objectives of Obamacare can be seen as such as in both cases the result is increased liberalization of the health care market. The very notion of "steering health policy" is Smithian in nature. Finally I do agree that the US government is not at all proactive in the managing of the health system and in fact I hope to see public provision of this service someday not laissez faire style behavior by government....Deon

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed