There is indeed a need for a paradigm shift in the practice of governance in the United States. No one is utterly satisfied with the way government is conducting its business. There is an across-ideology consensus that government should be free from special interests if it must operate effectively. To this, Osborne and Gaebler, the authors of the oft-cited book “Reinventing Government,” are absolutely right in alluding to Thomas Khun’s beloved concept: “paradigm shift”. Now, where controversy arises is whether the public spirit that guides government action should be converted into an entrepreneurial spirit where priorities are defined by competition or by what Hirschman calls “the availability of exit.”

Osborne and Gaebler’s book was first published in 1992. At that time, although the Democratic Party was in power, the revolution launched by the Reaganism in the 1980s to shrink the size of government was still in full-fledge effect. Al Gore, Clinton’s vice president, instituted what is known as National Partnership for Reinventing Government (NPR) on March 3, 1993. And the goal, as stated, was to “make the entire federal government less expensive and more efficient, and to change the culture of our national bureaucracy away from complacency and entitlement toward initiative and empowerment.” In other words, to use Osborne and Gaebler’s methaphor, government henceforth must steer not row. Government action should be reduced in a mere role of guiding and to a certain extent coordinating. Government agencies, the bureaucracy, should be defined in a competitive way; merit-based performance is the sole benchmark. Contracting out, privatization, competition to mention just three, constituted the new lexicon.

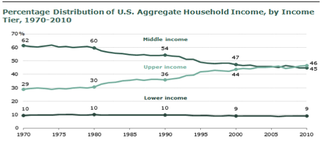

When, however, this new way of governance is scrutinized against empirical evidence, the results leave much to be desired. Research shows that the financial crisis that hit the country in 2008 with worldwide consequences is the result of this governance approach. The steering, or the passive role, of government in the financial sector (particularly the repeal of the Glass-Steagal Act) is considered to be the principal factor that led the world to the brink of this financial mess. Moreover, all statistical data seem to concur that from the 1950s to 1970s, when state interventionism was at its height, meaning when government was rowing, inequality of wealth and income was very moderate compared to the Reagan-Thatcher during which the legacy of the New Deals had been rolled back (Krugman, 2007). Figure 1 below shows the occurrence of a major shift in the income distribution after 1970. The 2012 Pew Research Center Report shows that upper-income households, as a proportion U.S. aggregate income, increase by 59% from 29% in 1970 to 46% of in 2010. Whereas, the share of the aggregate income by middle-income households decreases by 28% from 62% in 1970 to 45% in 2010. This situation is, according to many (Krugman, 2012; Stiglitz, 2012), associated with this model of governance.

As it happens, the claim to transform government into a market-like machine does not withstand empirical evidence and the practice falls short of expectations. The public sector is in essence different from other types of market organizations. While the market’s main function is to maximize net monetary benefit, protecting and promoting the public interest is (or should be) the core of all government action. Osborne and Gaebler’s entrepreneurial spirit paradigm aims at devising countless exit opportunities for the people in all settings: education, health, criminal justice, to mention a few. This should not be seen as bad propositions. After all, the American system is rooted in the tradition of finding exit opportunities for the people. However, as Hirschman adroitly points out, because they are usually made only on a short-run private interest calculus, individual exit decisions, in their aggregate effect, are harmful. For example, Hirschman says, “after an incipient deterioration of public schools or inner cities, the availability of private schools or suburban housing would lead, via exit, to further deterioration.” The existence of exit can, as it is often the case, impede voice that might be the best way for reform.

By Claude Joseph

Comment by Jermaine

Thanks for raising some of the costs of competition. With your post I am reminded of several stories that have come out that tell us about the implications of when the private sector competes and secures government contracts. There have been several stories about rapid increase in private sector run state prisons. While they have gained in securing more contracts, they have also gained by lowering the quality of service. Prisoners face telephone charges that are not competitive; prisoners are missing out on access to basic health services.

Osborne and Gaebler’s book was first published in 1992. At that time, although the Democratic Party was in power, the revolution launched by the Reaganism in the 1980s to shrink the size of government was still in full-fledge effect. Al Gore, Clinton’s vice president, instituted what is known as National Partnership for Reinventing Government (NPR) on March 3, 1993. And the goal, as stated, was to “make the entire federal government less expensive and more efficient, and to change the culture of our national bureaucracy away from complacency and entitlement toward initiative and empowerment.” In other words, to use Osborne and Gaebler’s methaphor, government henceforth must steer not row. Government action should be reduced in a mere role of guiding and to a certain extent coordinating. Government agencies, the bureaucracy, should be defined in a competitive way; merit-based performance is the sole benchmark. Contracting out, privatization, competition to mention just three, constituted the new lexicon.

When, however, this new way of governance is scrutinized against empirical evidence, the results leave much to be desired. Research shows that the financial crisis that hit the country in 2008 with worldwide consequences is the result of this governance approach. The steering, or the passive role, of government in the financial sector (particularly the repeal of the Glass-Steagal Act) is considered to be the principal factor that led the world to the brink of this financial mess. Moreover, all statistical data seem to concur that from the 1950s to 1970s, when state interventionism was at its height, meaning when government was rowing, inequality of wealth and income was very moderate compared to the Reagan-Thatcher during which the legacy of the New Deals had been rolled back (Krugman, 2007). Figure 1 below shows the occurrence of a major shift in the income distribution after 1970. The 2012 Pew Research Center Report shows that upper-income households, as a proportion U.S. aggregate income, increase by 59% from 29% in 1970 to 46% of in 2010. Whereas, the share of the aggregate income by middle-income households decreases by 28% from 62% in 1970 to 45% in 2010. This situation is, according to many (Krugman, 2012; Stiglitz, 2012), associated with this model of governance.

As it happens, the claim to transform government into a market-like machine does not withstand empirical evidence and the practice falls short of expectations. The public sector is in essence different from other types of market organizations. While the market’s main function is to maximize net monetary benefit, protecting and promoting the public interest is (or should be) the core of all government action. Osborne and Gaebler’s entrepreneurial spirit paradigm aims at devising countless exit opportunities for the people in all settings: education, health, criminal justice, to mention a few. This should not be seen as bad propositions. After all, the American system is rooted in the tradition of finding exit opportunities for the people. However, as Hirschman adroitly points out, because they are usually made only on a short-run private interest calculus, individual exit decisions, in their aggregate effect, are harmful. For example, Hirschman says, “after an incipient deterioration of public schools or inner cities, the availability of private schools or suburban housing would lead, via exit, to further deterioration.” The existence of exit can, as it is often the case, impede voice that might be the best way for reform.

By Claude Joseph

Comment by Jermaine

Thanks for raising some of the costs of competition. With your post I am reminded of several stories that have come out that tell us about the implications of when the private sector competes and secures government contracts. There have been several stories about rapid increase in private sector run state prisons. While they have gained in securing more contracts, they have also gained by lowering the quality of service. Prisoners face telephone charges that are not competitive; prisoners are missing out on access to basic health services.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed