Andrea

What is the driving force behind how and why policymakers make decisions? In an ideal policy environment, based upon the predicates of the rational model, policymakers will make informed decisions based on new information and lessons learned from past decisions made. However, as Gilardi (2010) finds, pre-existing ideologies may offset evidence indicating that an alternative policy is more effective or preferred than the current status quo. Ideology limits the value of new information and can impact the development of a policymaker’s stance on specific issues (652).

Today’s most emblematic manifestation of this tension is perhaps the current policy and political debate about the legalization of same sex marriage on the federal level. The Defense of Marriage Act, signed by President Bill Clinton in September 1996, restricts federal marriage benefits and inter-state marriage recognition to only opposite-sex marriages in the United States, thus denying same sex couples, even in states where their marriages are recognized, access to important benefits and protections. As more states have allowed same sex marriage, DOMA has entered increasingly murky territory in terms of its effectiveness as a policy. While marriage is usually a “states issue,” the role of federal policy in effectively nullifying the benefits intended to be afforded by states that allow same sex marriages has made the issue increasingly complex. Policymakers are at a crossroads: How can both federal and state policies be effective when one directly contradicts the premise of the other?

The cases currently being heard by the US Supreme Court have created an unprecedented policy window. Hollingsworth v. Perry seeks to have California’s Proposition 8, which bans same sex marriage, declared unconstitutional. United States v. Windsor seeks to allow protections and benefits given to opposite sex couples also extended to same sex couples. Either of these cases alone would perhaps draw enough attention to the issues at hand; together, they are doubly potent, particularly because each case addresses a different problematic component of current federal policy around same sex marriage.

Volden, et al. (2008), find that the policy windows create an opportunity for experimentation and innovation; and that during these periods policy innovations take place (326). They write, “Independent adoptions by states with different opportunities for change over time would also produce a spread of policy adoptions… simply because of differences in when their policy windows open” (326). Their finding is particularly relevant to the current policy landscape of same sex marriage, wherein theoretically each state can make its own legislative decisions. The states’ capacity is limited by the current federal policy restricting rights for same sex couples.

In the US, the spread of opinions about same sex marriage is vast and varied. States that have legislated same sex marriage on the whole have more progressive policymakers, while policymakers opposed to same sex marriage tend to represent states or districts with more conservative populations. The issue of pre-existing ideology, raised by Gilardi (2010), is certainly at play in the same sex marriage debate. For the most part, policymakers are primarily interested in being reelected, so the policies they support must reflect the ideologies of their electorate. At the same time, the policy window created by the attention being given the current Supreme Court cases has created an opportunity for innovation, particularly because the same sex marriage debate has called many long-standing ideological stances into question.

Resources

Gilardi, Fabrizio, “Who Learns from What in Policy Diffusion Processes?,” American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 2010.

Liptak, Adam, and Peter Baker. “Justices Cast Doubt on Benefits Ban in U.S. Marriage Law.” The New York Times. March 27, 2013.

Volden, Craig, Michael M. Ting, and Daniel P. Carpenter, “A Formal Model of Learning and Policy Diffusion,” The American Political Science Review, 102(3), 2008.

I think this example showcases in a very interesting way the complications of policy diffusion within the US federal system. Policy diffusion can occur for many reasons (imitation, competition, coercive forces etc.) but what becomes interesting through this exposé is the way this diffusion across states can contradict the federal policy system. Can we claim that in this case, the states are creating policy innovations that the federal policy system cannot or has not yet been able to internalize? I think this is an excellent example of the intricacies that often go along with the concept of policy diffusion but are not so often discussed in the literature.

Achilles

After four partial No-Smoking laws that have been largely ignored, failing to address the issue of smoking, in September 2010, Greece has voted a law banning smoking in enclosed public spaces. The decision to ban smoking was made after a series of similar laws adopted across the European Union, with Southern European countries (Portugal, Spain, Italy and finally Greece) being the last ones to enhance analogous regulations to the ones found in Northern European states. Perhaps the timing seemed right or the circumstances of policy diffusion were such that a convergence between national and euro-wide policies was possible; or maybe an actual policy window where the streams of problems politics and policies did collide to create the possibilities for such change. Nevertheless, three years after, and similarly to the prior four smoking prohibition plans, the law in Greece continues to be ignored. Public workers, including those in post offices and government buildings, as well as police, bus drivers or doctors in public hospitals continue to smoke without having to worry about being checked or having fines issued against them. Even members of the Parliament smoke openly in the building where they passed the ban, ironically ignoring their own law. What remains further puzzling is that this situation is idiosyncratic to Greece and not a generalized Southern European phenomenon. How can one explain this policy failure? Is it a consequence of “Greek lawlessness” or of a non-internalized –badly diffused policy?

As Weyland (2005: 262) notes, “one of the most striking phenomena in the area of public policy are the waves of diffusion that sometimes sweep across regions of the world.” The banning of smoking in many ways can be seen as a classic example of this process of policy diffusion. As scientific facts on the health externalities caused by smoking became even stronger, smoking gradually became a public health issue, to be addressed by holistic state or citywide public policies. And while policy diffusion scholars address the reasons of policy adoption through mechanisms such as Shipan’s and Volden’s learning, economic competition, imitation and coercion, they do not directly address failures such as the one described above. Certainly, one could argue that the adoption of the smoking ban in Greece was the result of learning: the likelihood of the policy to be adopted increases when the same policy was adopted by other states within the EU. From another lens, the adoption of the policy could be perceived as an imitation of the nearest neighbor or the trendsetter amongst states. In that sense, because imitation involves no concern about the effects of policies, but rather only a desire to do whatever a leader state has done, to paraphrase Shipan and Volden, Greece’s decision simply imitated the general trend and thus failed since the policy was not necessarily driven by the citizens will or demands for better public health through smoking regulation. Even adapting Grossback’s theory of US federalism to the European context by admitting that states learn from each other, but this learning depends more on the degree of ideological similarity between the states than the signals that come with region or mere adoption, we cannot possibly explain the reasons the policy although adopted in other similarly ideological countries, failed to go through in Greece.

But perhaps this ideological lens can help us identify what has been so different in the Greek context; while the banning in other countries has been perceived as a public policy aiming to ameliorate public health, in Greece the discussion took a very different turn. Right after the decision to vote for the banning a series of interest groups (restaurant and bar owners, local tobacco industries) posed the ban as an infringement to the personal liberties and rights of smokers. The law was perceived as imposed through a “patriarchal” state. Therefore the discussion followed a very different logic; one that displaced the attention from the positive effects of the banning to the normative perceptions of the role of the state. As Vardavas and Kafatos (2006) note the smoking problems of Greece adheres to the classic libertarian ideas of free will and choice of lifestyle. There is thus an inherent loath to comply with any laws that restrict personal freedom. The extent of this problem was also depicted in a pan-European health survey that assessed the newly introduced European guidelines on enforced labeling of health warnings on cigarette packages. Remarkably, the Greek male population was the only one in the European Union to regard the warnings as annoying, pointless, and invasive (Devlin et al.).

The example from Greece poses a serious question on the various theories of public policy diffusion. Certainly, we could argue that there are several mechanisms through which diffusion is achieved. But are there some mechanisms that seem to guarantee that the diffusion goes beyond the adoption and to the enforcement of the law?

References:

Devlin A, Anderson S, Hastings G, Macfadyen L. Targeting smokers via tobacco product labelling: opportunities and challenges for Pan European health promotion. Health Promot Int 2005; 20: 41-49

Gilardi Fabrizio, “Who Learns from What in Policy Diffusion Processes?”American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 2010

Shipan Charles R and Craig Volden, “The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion,”American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 2008

Vardavas C, A Kafatos, “Greece's tobacco policy: another myth?” The Lancet, Volume 367, Issue 9521, Pages 1485 - 1486, 6 May 2006

Nearly a decade following the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), state laws legalizing same-sex marriage began to arise. Have learning and diffusion played a role in the adoption of these policies and how has learning occurred?

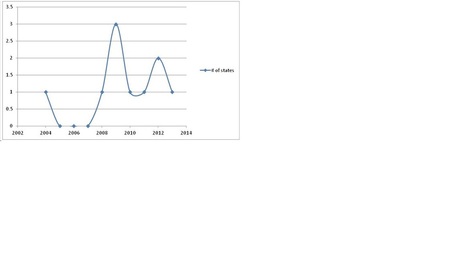

Currently, nine state governments, the District of Columbia and two tribes have legalized same-sex marriage. A number of other states allow same-sex unions that grant rights similar to marriage and many states ban same-sex marriage or other types of unions for same-sex couples. The graph below shows the number of states that legalized same sex marriage in each year since Massachusetts’s early adoption in 2004.

Although the time span over which these policies were adopted is far too short and the number of states that have adopted such policies are far too few to adequately observe trends, there does appear to be a slight time trend, with three states all adopting in 2009, then a lower but relatively steady number adopting between 2010-2013. This may support the imitation hypothesis, that states such as Connecticut and Vermont initially want to appear to be as innovative and progressive as Massachusetts and there is lag time for policy development to occur, but this effect fades over time (Shipan & Volden, 2008). The wave-like time and spatial clustering patterns that characterize U.S. states policy innovations and pension reforms in Latin American countries (Weyland, 2005) may also describe the spatial and time distributions of same-sex marriage policy adoption in the U.S. Currently, neighboring states tend to have more similar marriage policies, but this effect appears to taper off with distance from the center of similar policy clusters. However, if political ideology is considered, we might expect that the effect of spatial proximity is actually very weak.

With the exception of Iowa and New Hampshire, all states that have legalized same sex marriage voted Democrat in the last four presidential elections; Iowa and New Hampshire voted Democrat in three of the last four. In analyzing state lottery adoptions over >40 years, academic bankruptcy law adoptions over >10 years and sentencing guidelines adoptions over >10 years, Grossback et al. (2004) found that the effects of neighboring adoptions lost significance when accounting for ideology. In the case of states’ adoption of same-sex marriage laws, geographic proximity is also likely to be confounded with political ideology. Grossback et al. find that states which are ideologically similar to previous adopters are more likely to adopt and adoption by national government positively influences state adoption. This would suggest that conservative states are likely to be positively influenced by other conservative states that pass laws which ban same sex marriage, whereas liberal states that pass laws which legalize same sex marriage are likely to positively influence other liberal states into passing laws which legalize same sex marriage. It also suggests that DOMA has had a negative influence on states’ legalization of same-sex marriage.

However, Grossback et al.’s analysis does not consider the nature of the policy in question. In enacting DOMA, does national policy set an example, in some way coerce states, or spur policymakers to take a stand against federal legislation, as many policymakers believe that the federal government overstepped its bounds in enacting DOMA? Should we expect that policy issues involving conflicts between federal and state policy would involve the same learning and diffusion processes as those which do not involve such conflicts? Second, how does the nature of the policy affect the mechanism through which it will be learned or diffused? Policies which are more infused with ideology and which have smaller economic implications may be more subject to the influence of ideology when it comes to learning and diffusion. We should not necessarily expect that economic development policy and marriage policy would be influenced by ideology in the same way.

Zoé Hamstead

References

Grossback, L. J., Nicholson-Crotty, S., & Peterson, D. A. M. (2004). Ideology and Learning in Policy Diffusion. American Politics Research, 32(5), 521–545. doi:10.1177/1532673X04263801

Shipan, C. R., & Volden, C. (2008). The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 840–857.

Weyland, K. (2005). Theories of Policy Diffusion: Lessons from Latin American Pension Reform. World Politics, 57(2), 262–295.

Comment: This is an interesting application of policy diffusion theories to the socio-economic policy issue of same sex marriage. I think that while learning does play an important role in the diffusion of this policy throughout the states and indeed among countries. This learning process is constrained by the ideology of the states and countries that consider this issue. As you quite correctly pointed out all of the states who have legalized same sex marriage are "blue" which lends support to the conditional learning hypothesis. Furthermore globally same-sex marriage has been legalized in predominantly left governed countries. This I believe is more that just a coincidence.....Deon

This week, the New York Times’s Catherine Rampell muses about the efforts to improve highly-educated women’s presence, efficiency, and productivity in the US economy, in spite of the challenges posed by child birth and child rearing. Rampell noted the converging gender-parity policies being promulgated by the EU, individual european nations, and the US such as such as paid paternity leave, flexible scheduling, e-commuting, and on-site childcare. In the United States, with less of welfare state and less corporatist rapport between business and government than in Europe, similar initiatives have largely been adopted by progressive, wealthy states (California, New Jersey) or individual corporations, rather than nationally. Rampell also notes the relative dearth of US parity policies compared to Europe, indicating that a policy convergence may still be in its infancy. The normative importance of narrowing the pay and opportunity gaps between mothers and fathers ( a recent Government Accountability Office study shows that as of 2007, managers who are mothers are paid 79% of what managers who are fathers are paid) , is accompanied by expanded economic importance caused by declining workforces in developed countries. As Rampell notes, by 2050, the ratio of working-age Americans to those or retirement age is projected to decline from 4.7 in 2008 to 2.6 in 2050; further, she cites a recent study that attributes up to one fifth of recent economic growth to more efficient work allocations to underemployed groups, such as highly educated women. In short, the importance of maximizing the contributions of qualified workers will continue to grow in developed countries if we are to continue meeting our social obligations to ourselves and to compete in the global economy. This ongoing international discussion, as well as the convergence of policies aimed at eliminating the glass ceiling (or “diffusing the mommy bomb”) such as paid maternity and paternity leave, flexible hours, and on-site childcare, is shaped by, and possibly the product of, by globalization mechanisms. However, with roots in economic and normative arguments, it may be hard to fit the resultant policy convergences into only one of the prevailing convergence theories as defined by Daniel W. Drezner. It is clear that the motivation for these policies is not externally or structurally imposed, and therefore they are not a product of the Race to the Bottom or the World Society theories. While motivations for EU-based policy mechanism may be the result of Neoliberal cooperation, this is unlikely for convergences involving US and European policies, in which the benefits of such policies would not be shared (although the financial motivations for parity, and the perceptions of disparity as an economic externality, contribute to greater overlap with the Neoliberal theory). In this case, the closest theory would be the Elite Consensus theory, which fits the scenario only imperfectly. What if history documents that the prevailing motivation for this convergence is that as women gained level of parity in society and the workplace, including policymaking positions within States, National Governments, and large companies, they seek to redress a disparity which is naturally of interest to them using solutions gleaned from global counterparts? In that case, it would be agent based, and due to compositional and normative factors; this corresponds to the Elite Society theory, but the theory stipulates that interdependence precedes convergence (It is hard to imagine a situation in which New Jersey and Netherlands are economically interdependent on a level which affects regulations regarding professional mothers). In this case, the Elite Society theory may be overstating the importance of global interdependence in the diffusion of value-based policy advancements. References Drezner, Daniel W. Globalization and Policy Convergence. 2001. International Studies Association. The Government Accountability Office. Women in Management: Analysis of Female Managers’ Representation, Characteristics, and Pay. Sept 20 2010. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d10892r.pdf Rampell, Catherine. How Shared Diaper Duty Could Stimulate the Economy. April 2 2013. New York Times Online http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/07/magazine/how-shared-diaper-duty-could-stimulate-the-economy.html?_r=0

Early this year Republican Senator Stacey Campfield filed legislation in Tennessee House and Senate to connect Welfare benefits to children’s test scores.[i] The bill[ii] proposes that applicants for welfare, should they have children, be required to send their children to school, make sure they are immunized, and identify the father if child support is involved, which are already requirements of the Families First welfare in Tennessee.[iii] Additionally, the welfare office and each individual applicants will develop a “personal responsibility plan” where if any of the conditions are not met means a reduction in benefits. One of the conditions that should be included in each plan is that each child attend and “maintain satisfactory academic progress in school”. In order to reach this level, students need to fulfill school attendance requirements and receive a proficient or advanced score the state examinations in Math and English, Language and Arts (ELA) or maintain a grade point average that will allow the student to advance to the next grade. However, these requirements are not held to students who “have Individualized Educational Placements and who are not academically talented or gifted”. A failure of the student’s advancement to the next grade would stipulate a 30 percent reduction in benefits, until grades or scores are brought up. The majority of the conditions explicit in the legislation require nothing new of individuals seeking benefits; such legislation paints an undeserving and irresponsible picture of recipients. The negative emotions surrounding welfare benefits predate this legislation and on a whole are pervasive in American politics. For example, in European nations poverty is often linked to poor luck, and not lack of responsibility, as seen here, or initiative and hard work as argued by Nussbaum. [iv] This legislation, although only recommended at the state level, could influence national public policy. As the policy is more ideological than substantive in nature, it could be emulated in states or other nations that have similar ideological lines, particularly in those areas that this would only be an incremental policy innovation, like in Tennessee. [v] The implications of such a policy could be disastrous, particularly since interpretation of the child’s academic progress is ambiguously defined and determined by bureaucratic officials in the welfare office. Similarly, evidence that test scores can be equated to student progress or achievement is inconclusive. [vi] Lastly, the lowest achieving students are often the ones who are receiving welfare benefits and whether it is the fault of the parent or of failing schools, it does not seem appropriate to reduce the amounts of benefits children receive at home because of their inability to succeed in school. If the goal of the Republican Senator is to increase parent’s accountability in their children’s academic success, there are many public policy alternatives that he could support. For example, incentive based programs that reward academic achievement with after or out of school time programming, day care, or an increase in benefits might be more beneficial than cutting what little resources they are receiving from welfare. Ultimately in choosing an alternative policy one would need to decide whether a child should be held responsible for the quantity of foods stamps a family receives. Whether their fragile psyche should be held responsible for the quantity of support the state provides to their family, and what kind of stressors that would place on them and their familial relationships. Parent accountability in children’s academic success is important, but this seems like an alternative that is not simply about addressing accountability, but punitive in nature based on outdated ideological elucidations of the cause of poverty. [i] Healey, C. Tennessee Bill: Welfare Benefits Depends on Child’s School Performance. MSNBC, April 1, 2013. http://tv.msnbc.com/2013/04/01/tennessee-bill-welfare-benefits-depend-on-childs-school-performance/ [ii] Tennessee House Bill 0261: http://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/apps/billinfo/BillSummaryArchive.aspx?BillNumber=HB0261&ga=108 [iii] Application for Welfare benefits- Tennessee residents: http://www.tn.gov/humanserv/forms/Intake%20application%20and%20Statement%20of%20Understanding_English.pdf [iv] Nussbaum, M. “Upheavals of Thought”. Cambridge University Press, 2001. p 313 [v] Grossback, L. Ideology and Learning in Policy Diffusion. American Politics Research, Vol. 32, No. 5, September 2004. p522 [vi] “Class Size and Student Achievement: Research Review”. Center for Public Education. ND/np. http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/Main-Menu/Organizing-a-school/Class-size-and-student-achievement-At-a-glance/Class-size-and-student-achievement-Research-review.htmlKelsey

On the issues of Globalization, Immigration and Policy diffusion in the US, one might ask several questions. For example: Has globalization resulted in the convergence of US immigration policy with the policies of other OECD countries? If so why has this occurred? And which mechanisms facilitate the policy diffusion process on the global level? The readings this week may be used to frame these questions as one thinks about this important issue of immigration. In “Globalization and Policy Convergence” Drezner (2001) argues that while theories of policy convergence differ on whether the driving force is economic or ideational and whether states are able to retain agency, structurally based theories lack empirical support. Gilardi (2010) in “ Who Learns From What in the Policy Process?” argues that learning processes are likely to be conditional and highly influenced by the beliefs of policy makers whether these beliefs are prior or posterior. Shipman and Volden (2008) in “The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion” provides a discussion on the relative strengths of the four diffusion processes in influencing government. I would argue that there is indeed convergence in the immigration policies of the US, UK, Canada and Australia. Furthermore, while competitive and learning processes of policy diffusion are driving this convergence, it is delayed due to the conditional nature of the learning process.

Over the course of US history public policy towards immigration has changed. Immigration policy in the US is largely aimed at bringing immigrants who will be economically beneficial. As such immigration legislature has focused on three concerns; the ability of potential immigrants to find and hold jobs, their ability to adapt to American culture, and border security due to increasing occurrence of terrorist acts. Similarly in Canada the immigration system is focused on encouraging youthful, bilingual, high-skill immigration in order to build human capital within Canada’s labor force. As a result Canada has one of the highest net immigration rates in the world, greater than the UK, Australia and the United States. The aim of immigration policy in the UK is to enrich British culture and strengthen the economy while controlling immigration and the movement of people to protect the UK’s interests. As a result, British immigration policies are aimed at promoting multiculturalism and integration through anti-discrimination and education policies as well as religious diversity. The Australian Government operates a stricter and more rigid immigration policy that is aimed at achieving social and economic goals through the temporary and permanent movement of people and skills. Australian immigration authorities focus more on migrants who can demonstrate they will bring Professional, Trade or Business skills to Australia.

While immigration policy in these countries do differ, they do have some similarities that implies that there is some degree of policy diffusion. Moreover in contrast to policy diffusion at the state or municipal level the main mechanism driving this process is not learning and imitation but rather competition. As the main concern of the four OECD countries mentioned above is the attraction and retention of well-educated individuals that will bring social and economic benefits. Shipman and Volden (2008) disentangle for four mechanisms of policy diffusion: learning, imitation, competition and coercion. While some degree of learning in the policy diffusion process is taking place, one might argue that this learning is restrained by the specific conditions that exist in these countries. Gilardi (2010) makes a similar argument as he examines unemployment policies across 18 OECD countries. He shows that the diffusion process is influenced by whether the governing party is left or right in their ideology. In comparing immigration policy in Canada to the US, Canadian authorities must contend with a huge aging population that threatens the integrity of its economy while the US both historically, and more recently has had to consider border security. The UK on the hand has as its focus cultural and religious diversity while a second generation developed country like Australia must consider growth of its economy. Each of these themes acts to constrain the degree of learning in the policy diffusion process that will be undertaken in each country. US immigration policy for example should for example take into consideration the fact that it too faces an increasing aging population and could possibly benefit from the strategies implemented in the Canadian system. Yet a major part of its recent policy reforms have focused on security and border protection.

Despite the differences in the approaches to immigration policy it is quite clear that there is some degree of convergence between all four countries mentioned above. As they all recognize the importance of building up a highly skilled workforce that will enhance their social, cultural and economic structure. Moreover this policy convergence is largely due to globalization that facilitates the learning process while intensifying the role of competition in policy diffusion. Globalization not only promotes easy movement of capital and information but also the mobility of labor. Therefore in designing immigration policies these governments have been forced to consider the means for attracting and maintaining a youthful talented workforce. The degree of convergence is however slowed by domestic considerations in designing policy.

References

Drezner, Daniel W., “Globalization and Policy Convergence,” International Studies Review, 3(1), 2001

Gilardi Fabrizio, “Who Learns from What in Policy Diffusion Processes?” American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 2010

Shipan Charles R and Craig Volden, “The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion,” American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 2008

By Claude Joseph

Almost four decades ago, casinos were legal in only Nevada. Now, in one form or another, gambling is legal in every state except Hawaii and Utah (GAO, 2007). Casinos have expanded to the extent that the vast majority of Americans now have relatively access to one because they live within a three-to four-hour drive of a casino (Grinold & Mustard, 2004). This short essay is an attempt to shed light on the diffusion of legalized gambling across the American states in using appropriate existing theoretical frameworks.

Countless studies (Drezer, 2001; Grossback et. al., 2004; Meseguer, 2006) show that policy diffusion, defined as “the spread of policies or institutions across regions or globally”), does occur. Countries do not devise policies exclusively because of environmental pressure, policy choices of some countries are indeed influenced by others. However, coming to grips with what drives policy diffusion constitutes a contentious ground among scholars. While for some, the determinant of policy diffusion is transnational forces namely international financial institutions such as IMF and World Bank, others stick to the realist paradigm that states, despite the power of globalization, still have agency to enact policies. The state-oriented approach, in turn, is split into two categories. One, the constructivist approach, explains domestic initiative by a sort of symbolism, a desire to impress global opinion concerning a government capacity to innovate. The other, a goal oriented/problem-solving approach, argues that policy diffusion occurs because states pursue their self-interest. Wayland, for example, is not only subscribed to a state-centered paradigm, but also contends that policy diffusion is more likely to occur across neighbouring countries rather than globally. The reason is that governments are unable to scan the entire global environment; they instead use inferential shortcuts to search for good policies. To uphold his bounded learning framework, he uses the Chilean-style privatization. This argument, however, is challenged by Grossback et. al. (2004) who show that ideology (particular a sort of liberal-conservative divide) has more explanatory power than Wayland’s contiguity theory.

In this essay, I use the race-to-the-bottom (RTB) argument along with the bounded learning assumptions to explain the diffusion of legalized gambling across the American states.

Legalized gambling does, according to many, reduce budget deficit, and pay for important programs from public works to public education (Skolnik, 2011). These benefits are deemed to be in the public interest because they have positive impact on poor communities. From 1985 through June 1999, about $900 million of casino community reinvestment funds had been earmarked for community investment in Atlantic City including housing, road improvements, and casino hotel room expansion projects (GAO, 2000). As a result, state-level officials are turning to gambling as an economic cure-all and clamouring for more gambling in their respective states. A second related rationale for more gambling is that people from a state with no gambling will gamble in the proximate one that has legalized gambling. According to this perspective, states that do not legalize gambling will be economically left behind. This, consequently, leads to a race-to-the-bottom.

Our second assumption concerns the way a state, say Pennsylvania, learns about New Jersey gambling policy. To me, the former does legalize gambling not because a meticulous study that weighed the costs and benefits of gambling had been conducted on the policy enacted by the latter. Rather Pennsylvania’s policymakers, because of time constraints and insufficient information, use cognitive heuristics to make inference about the advantages and the side effects of gambling. I must also acknowledge that policy makers that form what Daniel Drezner dubs “epistemic community” are also influenced by pro- and anti-gambling lobbies – an issue that reinforces the explanatory power of bounded learning approach.

Comment

This is interesting. Policy diffusion seems to be a simple term that attempts to describe a very complex form of policy process. Sure, gambling may be in every state now. But what about issues of quality? What is the level of partnership between state government and American Indian tribes in states? Is the type of gambling similar or different between certain states? What's the consequence of the spread of gambling on economic and social well being of residents?Jermaine

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed