Nearly a decade following the passage of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), state laws legalizing same-sex marriage began to arise. Have learning and diffusion played a role in the adoption of these policies and how has learning occurred?

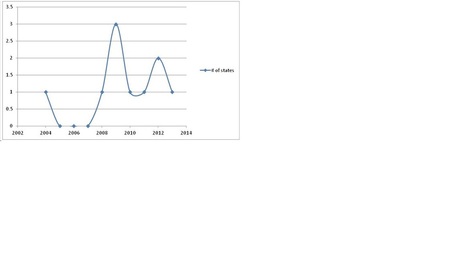

Currently, nine state governments, the District of Columbia and two tribes have legalized same-sex marriage. A number of other states allow same-sex unions that grant rights similar to marriage and many states ban same-sex marriage or other types of unions for same-sex couples. The graph below shows the number of states that legalized same sex marriage in each year since Massachusetts’s early adoption in 2004.

Although the time span over which these policies were adopted is far too short and the number of states that have adopted such policies are far too few to adequately observe trends, there does appear to be a slight time trend, with three states all adopting in 2009, then a lower but relatively steady number adopting between 2010-2013. This may support the imitation hypothesis, that states such as Connecticut and Vermont initially want to appear to be as innovative and progressive as Massachusetts and there is lag time for policy development to occur, but this effect fades over time (Shipan & Volden, 2008). The wave-like time and spatial clustering patterns that characterize U.S. states policy innovations and pension reforms in Latin American countries (Weyland, 2005) may also describe the spatial and time distributions of same-sex marriage policy adoption in the U.S. Currently, neighboring states tend to have more similar marriage policies, but this effect appears to taper off with distance from the center of similar policy clusters. However, if political ideology is considered, we might expect that the effect of spatial proximity is actually very weak.

With the exception of Iowa and New Hampshire, all states that have legalized same sex marriage voted Democrat in the last four presidential elections; Iowa and New Hampshire voted Democrat in three of the last four. In analyzing state lottery adoptions over >40 years, academic bankruptcy law adoptions over >10 years and sentencing guidelines adoptions over >10 years, Grossback et al. (2004) found that the effects of neighboring adoptions lost significance when accounting for ideology. In the case of states’ adoption of same-sex marriage laws, geographic proximity is also likely to be confounded with political ideology. Grossback et al. find that states which are ideologically similar to previous adopters are more likely to adopt and adoption by national government positively influences state adoption. This would suggest that conservative states are likely to be positively influenced by other conservative states that pass laws which ban same sex marriage, whereas liberal states that pass laws which legalize same sex marriage are likely to positively influence other liberal states into passing laws which legalize same sex marriage. It also suggests that DOMA has had a negative influence on states’ legalization of same-sex marriage.

However, Grossback et al.’s analysis does not consider the nature of the policy in question. In enacting DOMA, does national policy set an example, in some way coerce states, or spur policymakers to take a stand against federal legislation, as many policymakers believe that the federal government overstepped its bounds in enacting DOMA? Should we expect that policy issues involving conflicts between federal and state policy would involve the same learning and diffusion processes as those which do not involve such conflicts? Second, how does the nature of the policy affect the mechanism through which it will be learned or diffused? Policies which are more infused with ideology and which have smaller economic implications may be more subject to the influence of ideology when it comes to learning and diffusion. We should not necessarily expect that economic development policy and marriage policy would be influenced by ideology in the same way.

Zoé Hamstead

References

Grossback, L. J., Nicholson-Crotty, S., & Peterson, D. A. M. (2004). Ideology and Learning in Policy Diffusion. American Politics Research, 32(5), 521–545. doi:10.1177/1532673X04263801

Shipan, C. R., & Volden, C. (2008). The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 840–857.

Weyland, K. (2005). Theories of Policy Diffusion: Lessons from Latin American Pension Reform. World Politics, 57(2), 262–295.

Comment: This is an interesting application of policy diffusion theories to the socio-economic policy issue of same sex marriage. I think that while learning does play an important role in the diffusion of this policy throughout the states and indeed among countries. This learning process is constrained by the ideology of the states and countries that consider this issue. As you quite correctly pointed out all of the states who have legalized same sex marriage are "blue" which lends support to the conditional learning hypothesis. Furthermore globally same-sex marriage has been legalized in predominantly left governed countries. This I believe is more that just a coincidence.....Deon

With the exception of Iowa and New Hampshire, all states that have legalized same sex marriage voted Democrat in the last four presidential elections; Iowa and New Hampshire voted Democrat in three of the last four. In analyzing state lottery adoptions over >40 years, academic bankruptcy law adoptions over >10 years and sentencing guidelines adoptions over >10 years, Grossback et al. (2004) found that the effects of neighboring adoptions lost significance when accounting for ideology. In the case of states’ adoption of same-sex marriage laws, geographic proximity is also likely to be confounded with political ideology. Grossback et al. find that states which are ideologically similar to previous adopters are more likely to adopt and adoption by national government positively influences state adoption. This would suggest that conservative states are likely to be positively influenced by other conservative states that pass laws which ban same sex marriage, whereas liberal states that pass laws which legalize same sex marriage are likely to positively influence other liberal states into passing laws which legalize same sex marriage. It also suggests that DOMA has had a negative influence on states’ legalization of same-sex marriage.

However, Grossback et al.’s analysis does not consider the nature of the policy in question. In enacting DOMA, does national policy set an example, in some way coerce states, or spur policymakers to take a stand against federal legislation, as many policymakers believe that the federal government overstepped its bounds in enacting DOMA? Should we expect that policy issues involving conflicts between federal and state policy would involve the same learning and diffusion processes as those which do not involve such conflicts? Second, how does the nature of the policy affect the mechanism through which it will be learned or diffused? Policies which are more infused with ideology and which have smaller economic implications may be more subject to the influence of ideology when it comes to learning and diffusion. We should not necessarily expect that economic development policy and marriage policy would be influenced by ideology in the same way.

Zoé Hamstead

References

Grossback, L. J., Nicholson-Crotty, S., & Peterson, D. A. M. (2004). Ideology and Learning in Policy Diffusion. American Politics Research, 32(5), 521–545. doi:10.1177/1532673X04263801

Shipan, C. R., & Volden, C. (2008). The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 840–857.

Weyland, K. (2005). Theories of Policy Diffusion: Lessons from Latin American Pension Reform. World Politics, 57(2), 262–295.

Comment: This is an interesting application of policy diffusion theories to the socio-economic policy issue of same sex marriage. I think that while learning does play an important role in the diffusion of this policy throughout the states and indeed among countries. This learning process is constrained by the ideology of the states and countries that consider this issue. As you quite correctly pointed out all of the states who have legalized same sex marriage are "blue" which lends support to the conditional learning hypothesis. Furthermore globally same-sex marriage has been legalized in predominantly left governed countries. This I believe is more that just a coincidence.....Deon

RSS Feed

RSS Feed